Introduction

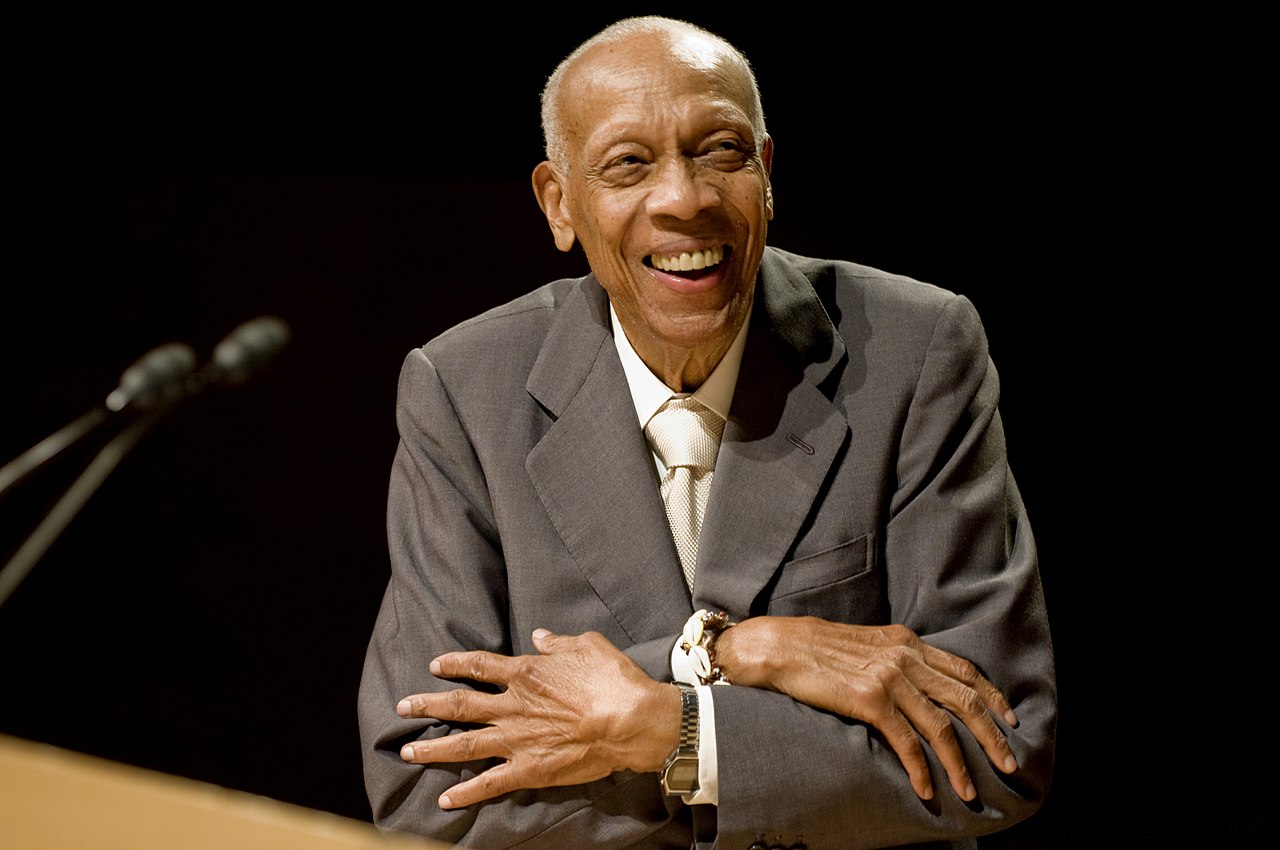

Bebo Valdés (1) has built a

brilliant career based on his works. He had close friendships with

figures who transformed Latin jazz and Cuban music—musicians from the

late 19th century like "Samuel," "Cervantes," and "Romeu." Despite

being 91 years old and suffering from arthritis, his nimble fingers

are still capable of performing complex musical scales and the fast

dance rhythms of "Mambo" (2), which

was pioneered by "Cachao López"

(3).

Since the time flamenco musicians welcomed him into their community

with open arms, Bebo's musical spirit has become more alive and has

soared. With an extraordinary expressive brilliance in his piano

playing, Bebo began collaborating with the renowned flamenco singer

"Diego El Cigala" (4). The result

of this collaboration was the highly successful album Lágrimas Negras

(Black Tears) (5)—a brilliant and

exceptional album that brings various musical styles together before

us, offering a magical taste of folk and tribal music. Here, flamenco

singing and the sound of the instruments chase each other, find each

other, caress each other, embrace, and ultimately merge into a unique

dream.

Source: flamenco-world.com

Interview with Bebo Valdés

At certain points, you have been influenced by Spanish music. Which

type of music has had the greatest impact on you?

Bebo Valdés: The music of old composers like Manuel de Falla, Joaquín

Turina, and Isaac Albéniz. Falla, because of his arrangements—he

applied a French technique to Spanish music. I think he was a student

of Albéniz. I also love Albéniz and Turina. Their music touched my

heart. However, if I had to choose one among them, I would say Falla.

I think he was the best of them all.

Was it flamenco that sparked your love for Spanish music in your

youth?

Bebo Valdés: (Laughs) You could say that. But it took years for me to

move from the influence of those old composers to flamenco, and that

happened when a child named Diego El Cigala heard me playing Lágrimas

Negras alongside my son "Chucho"

(6) and Cachao López. He said he

wanted to learn, and I told him—why not start from the foundation?

Thus, our first meeting took place at the house of "Fernando Trueba."

While playing alongside Diego’s singing, I realized the incredible

similarities between Cuban and Spanish music. For example, there is a

"Malagueña" rhythm that is exactly like our Cuban "Guaguancó"

(7). There are many other rhythmic

and harmonic similarities, influenced by both African and Indian

music. So, naturally, we started playing Bolero

(8), Seguirilla

(9), and Guajira

(10) together.

However, beyond the connection between flamenco and Afro-Cuban

music (11), there are other

similarities—such as the relationship between tango and "Comparsa"

(12), or the resemblance

between Rumba Flamenca (13) and

the songs that were sung in the Yoruba

(14) language…

Bebo Valdés: Yes, I agree. I believe all of this originates from the

migration to Cuba that began in 1509, accompanied by colonization. We

must not forget that the two-beat Cuban dance music, Habanera

(15), came from Spain to Cuba. A

similar thing happened with Contradanza

(16) when Habanera made its way

from Spain to Havana, Contradanza arrived from Haiti and France to

Santiago de Cuba. The Haitian landowners settled in Santiago and

Guantánamo, bringing their enslaved people with them. These Africans,

who were forced to work on sugarcane plantations, carried with them a

unique kind of music, among which we can mention an African form of

Contradanza and the Changüí

(17) music. However, there is

much debate over the true origins of Contradanza. Some music scholars

claim it originates from England, but personally, although I cannot

prove it, I strongly believe this music is 100% French in origin.

Let's move from this discussion to modern music. Let's talk about

"Paquito D'Rivera" (18) the

person responsible for bringing you back to the stage after twenty

years of isolation…

Bebo Valdés: Paquito called me one day in 1994 and asked for my help.

He needed to perform a music program and required some good, authentic

pieces. I told him, "I am far from what you are asking—I haven’t

composed anything in years." He then asked me, "But do you have any

new ideas for a project?" I said, "Well... I have a few!" So I got to

work, and within 36 hours, I had composed several pieces, including

Oleaje (19), which I wrote for

solo piano. Although the album belonged to Paquito, he gifted me the

rights to it, and that’s how Bebo Cabalga de Nuevo! (Bebo Rides Again)

(20)

In the 1940s and 1950s, before the Cuban Revolution, you were a

highly active figure in music. What do you remember from that

era?

Bebo Valdés: Back then, many Cubans frequently traveled to the United

States, especially from November to March. They had to perform in

casinos. At that time, I played jazz, though I was also deeply

fascinated by street dances like Boogie-Woogie

(21), Danzón

(22), and Rumba. Then, in 1937,

Cachao López and I formed an orchestra. It must be acknowledged that

Cachao reinvented the music and dance of Mambo in his own way. His

orchestra continued, but I focused on my studies. In 1943, I joined

the "Corbelito" music group. At that time, I was nearing the end of my

studies. I had completed my studies in harmony and was about to begin

my research in counterpoint

(23) and orchestration.

Wasn't that the time when jazz legend "Norman Granz"

(24) invited you to record a

piece?

Bebo Valdés: That happened a bit later, in 1952. I never met him in

person. There were strong influences from American society on Cuban

music. Granz hired me, and we recorded the first Cuban music piece in

history together. About a month later, the piece was recorded in a

studio in Havana, but Granz wasn’t there. I don’t know why he couldn’t

supervise the recording. Regardless, it was a unique Cuban music

recording. There was sugarcane rum and beer. It was amazing!

We've sometimes noticed that Afro-Cuban jazz is not exactly the

same as Latin jazz. What are the differences between these two jazz

styles?

Bebo Valdés: Afro-Cuban jazz was precisely our improvisations based on

Cuban rhythms, exactly what Mario Bauzá

(25) was doing in the U.S. But

the main issue was the financial and commercial aspect because the

term Latin jazz was more appealing to South American record companies.

That title referred to the entire South American continent, which

naturally led to higher sales.

Given that, don’t you think musicians like Xavier Cugat or Dámaso

Pérez Prado diluted the rhythmic complexity of Cuban music—something

that was truly present in Afro-Cuban jazz—and sacrificed it under

the label of Latin jazz for economic reasons?

Bebo Valdés: Well, I can’t really speak about Pérez Prado

specifically. He was born in Matanzas and made excellent arrangements,

especially when he moved to Mexico. Maybe when he became very famous,

he compromised on quality to some extent. As for Xavier Cugat, he was

more of a caricaturist and a Hollywood figure than a musician,

although he was highly successful in entertainment and made more money

than any other Cuban musician!

But Beny Moré (26)! The voice

of Cuban music! A person who was truly a musician rather than a

businessman. Is it true that when Beny Moré saw your son, Chucho

Valdés, playing the piano, he told you: “Hey! This kid is going to

play the piano even better than you!”?

(laughs) That’s exactly what he said… I met Beny in 1945. At that

time, I was working in a radio station’s music group and writing

arrangements for songs. We needed a singer because our previous singer

had fallen ill, so Beny Moré replaced him. He was truly a talented

man. No one expected him to rise from being a street guitarist to

having his own orchestra. However, although Beny knew how to lead his

orchestra, he wasn’t technically a conductor. The one who took on that

role was Generoso Jiménez, who wrote the arrangements for Beny. When I

released the Batanga album, he came to me looking for work because he

had been fired. I talked to Paquito Gutiérrez, and that was when we

started our work at the radio station. After that, Beny Moré truly

shined.

If we want to talk more about Bebo, we cannot overlook the Valdés

family's piano legacy. Your son, Chucho, is a well-known pianist.

What about your granddaughter, Chucho’s daughter?

Bebo Valdés: Yes, it’s unbelievable! Diana, Chucho’s daughter, won

first prize in a classical piano competition in Italy at the age of

19. She is considered the most important treasure of Chucho’s life. A

little while ago, Chucho introduced her to me. She looked into my eyes

and declared that she intended to follow in the musical footsteps of

her father and me in jazz. But she didn’t say this to ask for help—she

expressed it with all her heart. In fact, she was asking me to

convince Chucho to let her pursue such a path. And now, I tell you, we

have an appointment together. At the San Sebastián Jazz Festival on

July 27. First, Chucho will perform with his group, then I will take

the stage with Cigala. Apparently, we are going to witness a

three-piano duel: me, my son Chucho, and my granddaughter Diana.

Some critics have pointed out that your piano style is more related

to the 19th-century neoclassical style, like that of pianists such

as Romeo and Samuel, rather than 20th-century piano playing...

Bebo Valdés: This question is generally about style. When I released

the Batanga album, everyone said that this style was the future of

Cuban piano playing. But I could never forget the playing of "Ernesto

Lecuona" and Romeo. They created a domain that all of us walk upon

today.

Let’s focus on the album you recently released with Diego Cigala,

Lágrimas Negras. In this album, for the first time, Cuban bolero

music was combined with Spanish flamenco. What led you to release an

album in the bolero style, and why did you choose the title Lágrimas

Negras (Black Tears)?

Bebo Valdés: The name Lágrimas Negras was chosen because it belongs to

a famous classic bolero song composed by Miguel Matamoros

(27). We wanted to have a

different interpretation of this song, distinct from the hundreds of

existing versions. Moreover, Cigala is crazy about this song… and in

love with every bolero, really. I have played these songs all my life.

I can say that people were deeply moved by this performance. This

album has highly emotional pieces. At times, listeners are touched and

brought to tears, and at other times, they feel lively and cheerful.

When you play different styles, how do you adapt them to the

piano?

Bebo Valdés: On the surface, I don’t change anything in the style. I

try to capture the form. I might modify the melodies slightly for

embellishment. I learn a lot from flamenco musicians. I find myself

among Diego Cigala and others, entering their world. And they enter

mine. Look… they gave me a gift. (He proudly shows a medal pinned to

his right chest.) This medal belongs to the Brotherhood of the Gypsies

of Almería (28). They told me

that I am one of them. And I told them the same thing. (He pauses

briefly.) It’s unbelievable how musical they are. For example, take

"Niño Josele" (29). He has never

attended a conservatory, yet he is one of the finest performers on

stage.

As a final question, what plans do you have for the future?

Bebo Valdés: I don’t have any long-term projects for the future, but

at the moment, I have many plans. With God's help, I intend to work as

much as I can. At my age, I cannot make long-term plans. Months go by,

and I count them… but who cares? Because just this year, I have

recorded three new albums! One with my own group, one as solo piano

and violin performances, and another with a nine-member ensemble. Each

album represents a different aspect of me. These projects were

suggested to me by Nat Chediak and Trueba, and fortunately, they were

possible. And now, I ask God to help us continue working together for

as long as possible.

Footnotes

(1) Bebo Valdés, the legendary

Cuban pianist, bandleader, and composer, pivotal in the development of

Cuban jazz and mambo. His innovative style and collaborations,

particularly left an indelible mark on Latin music.

go back

(2) Mambo: A type of Cuban dance

and music. The word originates from the Yoruba language, spoken by

African slaves brought to Cuba, meaning "conversation with the gods."

Mambo is a Latin American music style that emerged in the 1930s,

pioneered by Cachao López and some of his contemporaries, such as Beny

Moré. This music was performed in Havana casinos.

go back

(3) Cachao López: Known as

"Cachao," he was a musician and bass player in mambo music and played

a crucial role in popularizing mambo in the early 1950s in the U.S. He

won multiple Grammy Awards and is recognized as the inventor of mambo.

go back

(4) Diego El Cigala: Diego Ramón

Jiménez Salazar, a renowned flamenco singer, known as "El Cigala,"

meaning "Norwegian lobster." He stated that three Guitarists gave him

this nickname, referring to his extreme thinness! He won a Grammy

Award with Bebo Valdés for their album Lágrimas Negras (Black Tears).

go back

(5) Lágrimas Negras: a classic

Cuban bolero that blends traditional melodies with poignant lyrics of

heartbreak. Its enduring popularity stems from its emotional depth and

the captivating performances it has inspired.

go back

(6) Chucho Valdés: A highly

acclaimed Cuban pianist and composer, renowned for his virtuosic blend

of jazz, classical, and Afro-Cuban musical traditions. His innovative

contributions to Latin jazz have earned him numerous Grammy Awards and

solidified his status as a musical legend. go back

(7) Guaguancó: A Cuban dance

featuring highly complex movements with a fast rhythm. This music

involves Cuban percussion instruments accompanied by a solo singer and

a chorus. Additionally, a male and a female dancer perform along with

the music. go back

(8) Bolero: A slow-tempo dance

common in Spain and Cuba, with a history of over a century. The

Spanish and Cuban versions of this dance are distinct. It typically

has a 3/4 rhythm. go back

(9) Seguirilla: A Spanish dance

also found in Cuba, often featuring minimal lyrics but enriched with

wailing and lament-like sounds. It is a solo dance that must be

performed with intense emotion. This dance is solemn, harsh, and

deeply expressive, often associated with traditional and ritualistic

ceremonies. The surroundings should be simple and unadorned. The

rhythm is slow yet complex. go back

(10) Guajira: A Cuban music style

with rural-themed lyrics. It is usually performed in 3/4 or 6/8 time

by a singer accompanied by a Guitar. The lyrics often describe the

beauty of rural landscapes. go back

(11) Afro-Cuban Music: Cuban

music with African roots. In practice, Cuban music as a whole is

deeply influenced by African traditions, making this term broadly

applicable to Cuban music. go back

(12) Comparsa: A theatrical and

highly visual dance performed as a street festival. Performers and

dancers move to the sound of drums and the voices of singers known as

Conga. A panel of judges selects the best performers.

go back

(13)Rumba Flamenco: A style of

Flamenco music influenced by Afro-Cuban music. This influence traveled

from Cuba to Spain in the 19th century. In Spain, it is performed with

Guitar and hand claps, while in Cuba, it incorporates percussion

instruments. go back

(14) Yoruba: A widely spoken West

African language brought to Cuba by African slaves. More than 25

million people in Africa speak Yoruba. It is commonly used in

songwriting and composing. go back

(15) Habanera: A Cuban dance from

the 19th century characterized by the Habanera rhythm, accompanied by

song lyrics. It follows a 2/4 time signature, with a dotted eighth

note, a sixteenth note, and two eighth notes in each measure. It was

the first Cuban dance exported worldwide. go back

(16) Contradanza: An 18th-century

English-origin dance, performed by the French, English, and Germans in

the 19th century. It is designed for multiple dancing couples. It was

a dance of the aristocracy. go back

(17) Changüí Sound: A dance

popular in eastern Cuba in the early 20th century. It emerged

alongside the fusion of Spanish Guitar and African rhythms and was

especially common in the Guantánamo province.

go back

(18) Paquito de Rivera: A Cuban

musician, alto Saxophonist, soprano Saxophonist, and Clarinetist,

winner of multiple Grammy Awards. go back

(19) Oleaje: A captivating piano

piece that showcases his mastery of blending Cuban rhythms with jazz

improvisation, evoking the rolling, powerful movement of ocean waves.

go back

(20) Translation of the album's

title in Spanish "Bebo Cabalga de Nuevo". go back

(21) Boogie-Woogie: A six-beat

rhythm dance popular in Europe between the 1930s and 1950s.

go back

(22) Danzón: The national and

official dance of Cuba, introduced by French immigrants who fled the

Haitian Revolution. go back

(23) Counterpoint: The technique

of setting, writing, or playing a melody or melodies in conjunction

with another, according to fixed rules. go back

(24) Norman Granz: A famous

American jazz musician and music producer in the 1950s and 1960s.

go back

(25) Mario Bauzá: A Cuban

musician active in the U.S. in the 1930s, among the first to introduce

Cuban music to America. go back

(26) Benny Moré: A Cuban singer

(1919–1963), considered by many as the greatest Cuban singer of all

time. Due to his mastery of various musical styles, he was given many

titles, including Bárbaro del Ritmo ("The Wild Man of Rhythm").

go back

(27) Miguel Matamoros, Cuban

composer and Guitarist (1894–1971). go back

(28) Almería: A province in

southeastern Spain on the Mediterranean coast.

go back

(29) Niño Josele: A Spanish

Guitarist and innovator of the Neoflamenco style.

go back